Clustered and Non-Clustered Implementations

Introduction to Database Indexing

Database indexes help the database locate data faster by reducing the amount of data that must be read from disk.

Without an index, the database engine performs a table scan, which means reading every data page and evaluating each row until the query condition is satisfied. This approach is acceptable for very small tables but quickly becomes a bottleneck as data volume grows.

Indexes exist to avoid this cost by allowing the engine to jump directly to relevant pages.

Indexes improve:

- Query performance by reducing I/O

- Sorting efficiency by maintaining ordered structures

- Join performance by enabling fast lookups

- CPU usage by minimizing row evaluations

- Overall system throughput under concurrent load

Internally, an index is a data structure that maps key values to row locations. The database optimizer decides whether to use an index based on cost estimation, not based on whether the index exists.

Creating the right index is not about indexing everything. It is about indexing access patterns.

Clustered and Non-Clustered Implementations

A table can be organized in two fundamental ways:

- Physically ordered by a clustered index

- Unordered as a heap with optional non-clustered indexes

Understanding how each option affects storage, reads, and writes is critical for designing scalable schemas.

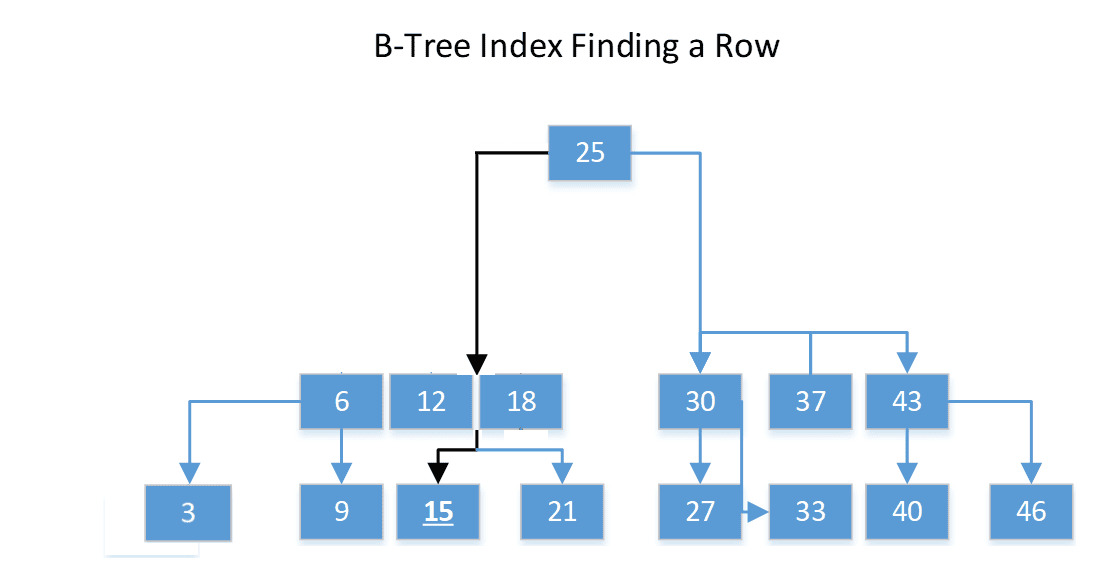

B-Tree Architecture: How Indexes Work

Most relational databases use B-Tree structures for indexes. This includes SQL Server, PostgreSQL, MySQL (InnoDB), and Oracle.

A B-Tree keeps data balanced and shallow, which guarantees predictable performance even as tables grow to millions or billions of rows.

Key properties:

- All leaf nodes are at the same depth

- The tree remains balanced automatically

- Lookups require a small number of page reads

How a B-Tree Works

- The root node contains key ranges

- Intermediate nodes narrow the search range

- Leaf nodes contain either data rows or row locators

- Each page stores multiple keys to reduce tree height

Because of this design, index operations scale logarithmically with data size.

Operation Complexity

Operation Complexity Description

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Equality Seek O(log n) Direct lookup by key

Range Query O(log n + k) k = number of rows returned

Insert O(log n) May cause page split

Delete O(log n) May cause page merge

In practice, most index seeks require only 2 to 4 page reads, even for very large tables.

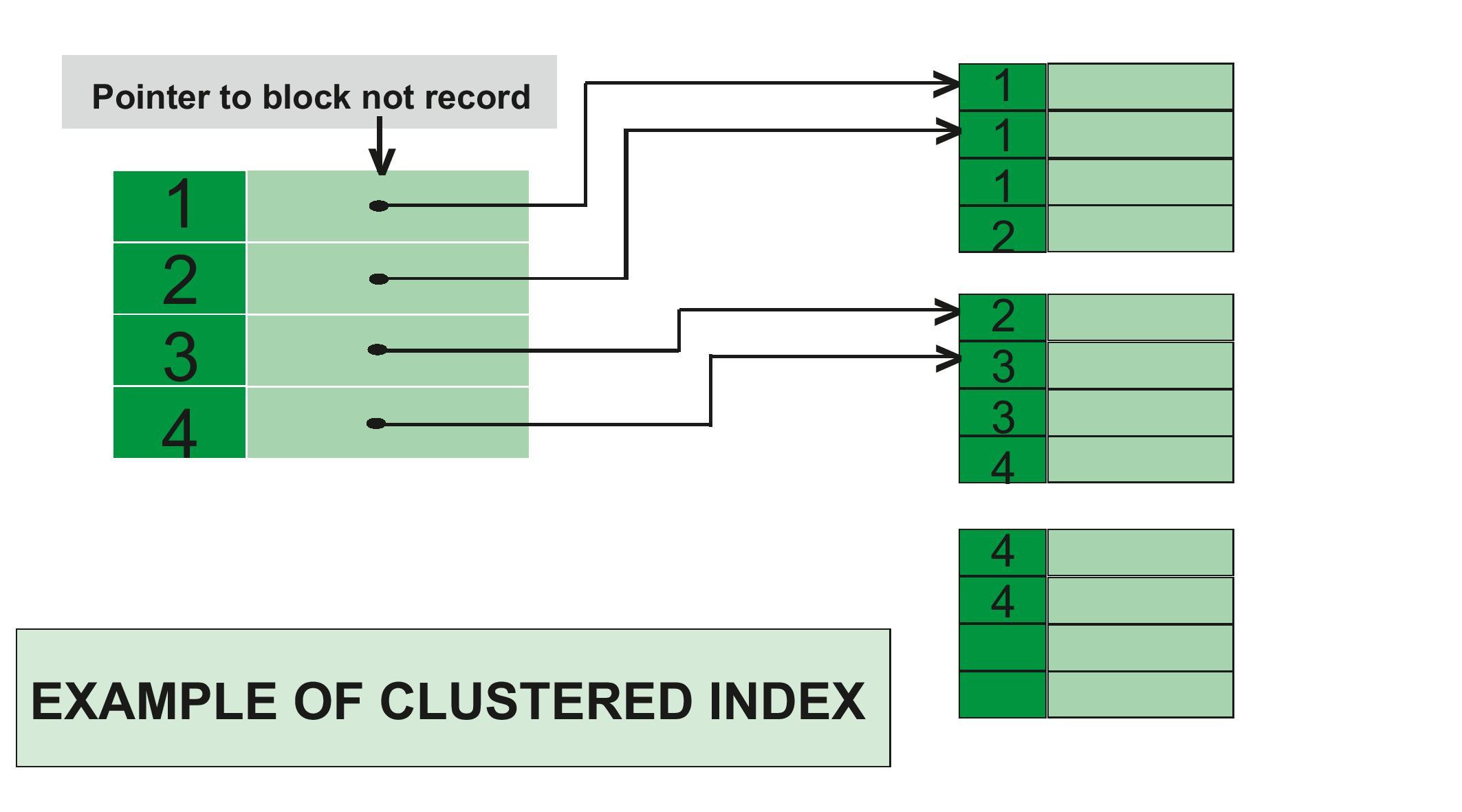

Clustered Indexes

A clustered index defines the physical order of rows on disk.

When a table has a clustered index, the leaf level of the B-Tree is the table itself. There is no separate data structure for the table rows.

Because data can only be physically ordered one way, a table can have only one clustered index.

Key Characteristics

- Data pages are sorted by the clustered key

- Non-unique keys are made unique using an internal uniquifier

- Range queries are extremely efficient

- Large inserts benefit from sequential keys

- Page splits occur when inserting into the middle of the key range

Example

CREATE CLUSTERED INDEX IX_Orders_Date

ON Orders (OrderDate);

This layout is ideal for queries such as:

SELECT *

FROM Orders

WHERE OrderDate BETWEEN '2024-01-01' AND '2024-01-31';

What Happens on Disk

Page 1023 -> rows for 2024-01-01

Page 1024 -> rows for 2024-01-02

Page 1025 -> rows for 2024-01-03

The engine reads pages sequentially, which is optimal for disk and memory access.

Choosing a Good Clustered Key

A good clustered key should be:

- Narrow (few bytes)

- Immutable (rarely updated)

- Sequential when possible

- Frequently used in range queries

Bad clustered keys include GUIDs generated randomly and frequently updated columns.

Fill Factor

Fill factor controls how much free space is left on index pages during creation or rebuild.

CREATE CLUSTERED INDEX IX_Customers_Cluster

ON Customers (LastName)

WITH (FILLFACTOR = 90);

Lower fill factors reduce page splits at the cost of higher storage usage.

Composite Clustered Index

Composite keys allow finer control over ordering.

CREATE CLUSTERED INDEX IX_Orders_Composite

ON Orders (OrderDate DESC, OrderID ASC);

This supports stable ordering when multiple rows share the same date.

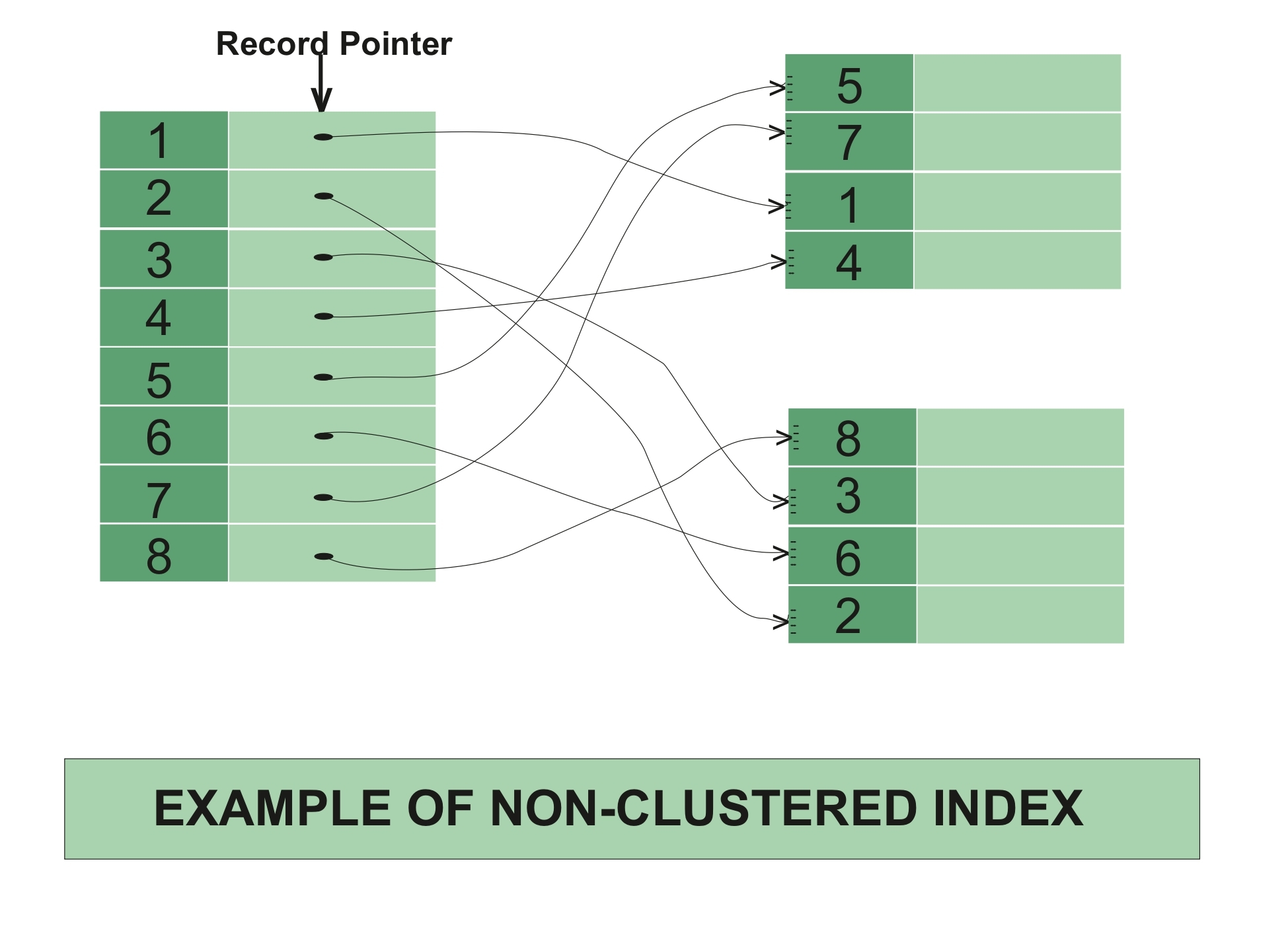

Non-Clustered Indexes

A non-clustered index is a separate structure that stores keys and row locators.

Unlike clustered indexes, the leaf level does not contain full rows.

What it stores depends on the table type:

- Heap: row identifier (RID)

- Clustered table: clustered key value

Example

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX IX_Orders_Customer

ON Orders (CustomerID)

INCLUDE (OrderDate, TotalAmount);

This index supports queries that filter by CustomerID and select included columns without touching the base table.

Storage Layout Example

Index Page:

CustomerID | Row Locator

12345 | ClusteredKey = (2024-01-02, 89123)

12346 | ClusteredKey = (2024-01-05, 89188)

Key Lookups

If a query selects columns not present in the index, the engine performs a key lookup to fetch the remaining columns from the clustered index.

Covering indexes eliminate this cost.

Specialized Index Types

Filtered Index

Filtered indexes store only a subset of rows.

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX IX_Users_Active

ON Users (LastLoginDate)

WHERE IsActive = 1;

Benefits:

- Smaller size

- Faster seeks

- Lower maintenance cost

Best used when predicates are stable and selective.

Columnstore Index

Columnstore indexes store data by column instead of by row.

CREATE COLUMNSTORE INDEX IX_Sales_Columnstore

ON Sales (ProductID, SaleDate, Quantity, Amount);

They are optimized for:

- Aggregations

- Scans over large datasets

- Analytics and reporting workloads

They are not ideal for heavy OLTP updates.

Index Selection Guide

Scenario Recommended Index Reason

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Primary Key Clustered Natural ordering

Range Queries Clustered Sequential reads

Frequent Lookups Non-Clustered Fast seeks

Covering Queries Non-Clustered + INCLUDE Avoids lookups

Low Cardinality Filters Filtered Index Smaller footprint

Analytics Columnstore Compression and scans

Index Maintenance

Over time, inserts and deletes cause fragmentation.

Fragmentation increases:

- Page reads

- Memory usage

- CPU overhead

Maintenance Strategy

- Reorganize when fragmentation is between 5 and 30 percent

- Rebuild when fragmentation exceeds 30 percent

Smart Maintenance Script

DECLARE @IndexName NVARCHAR(255), @Fragmentation FLOAT

DECLARE IndexCursor CURSOR FOR

SELECT name, avg_fragmentation_in_percent

FROM sys.dm_db_index_physical_stats(DB_ID(), NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL) ps

JOIN sys.indexes i

ON ps.object_id = i.object_id AND ps.index_id = i.index_id

WHERE ps.avg_fragmentation_in_percent > 5

OPEN IndexCursor

FETCH NEXT FROM IndexCursor INTO @IndexName, @Fragmentation

WHILE @@FETCH_STATUS = 0

BEGIN

IF @Fragmentation > 30

EXEC('ALTER INDEX ' + @IndexName + ' ON Orders REBUILD')

ELSE

EXEC('ALTER INDEX ' + @IndexName + ' ON Orders REORGANIZE')

FETCH NEXT FROM IndexCursor INTO @IndexName, @Fragmentation

END

CLOSE IndexCursor

DEALLOCATE IndexCursor

Performance Comparison (10M Rows)

Operation Clustered Non-Clustered Heap

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Primary Key Seek 0.003 ms 0.003 + lookup 2.1 ms

Range Query (10k rows) 12 ms 45 ms 1200 ms

INSERT (sequential) 8 ms 10 ms 5 ms

INSERT (random) 120 ms 15 ms 5 ms

UPDATE (in-place) 6 ms 9 ms 7 ms

Advanced Index Patterns

Indexed View

Indexed views materialize aggregations.

CREATE VIEW dbo.OrderSummary WITH SCHEMABINDING AS

SELECT CustomerID, COUNT_BIG(*) AS OrderCount, SUM(TotalAmount) AS Total

FROM dbo.Orders

GROUP BY CustomerID;

CREATE UNIQUE CLUSTERED INDEX IX_OrderSummary

ON dbo.OrderSummary (CustomerID);

They are useful for expensive aggregations with stable data.

Partitioned Index

Partitioning improves manageability and query pruning.

CREATE PARTITION FUNCTION OrderDateRangePF (DATE)

AS RANGE RIGHT FOR VALUES

('2024-01-01', '2024-02-01', '2024-03-01');

Often combined with sliding window strategies.

Troubleshooting Index Problems

Useful diagnostics:

SET STATISTICS XML ON;

SELECT * FROM sys.dm_db_missing_index_details;

SELECT * FROM sys.dm_db_index_usage_stats;

Never create indexes blindly based only on missing index suggestions.

Conclusion

A strong indexing strategy balances:

- Read performance

- Write cost

- Storage usage

- Maintenance overhead

Practical rules:

- Choose clustered keys deliberately

- Use non-clustered indexes to support query patterns

- Cover critical queries with INCLUDE

- Remove unused indexes regularly

- Maintain indexes based on fragmentation metrics

Indexes are not optional optimizations. They are a core part of database design.